Corbyn at the Aneurin Bevan Stones at Bryn Serth, 11 August (Tredegar Forum)

by Merlin Gable

in the OLR blog series on the Corbyn Campaign

One wonders whether there has been a political rally more like preaching to the converted than Corbyn’s at the Aneurin Bevan Memorial Stones near Ebbw Vale in the South Wales Valleys. A safe Labour seat, an old Labour seat, Blaenau Gwent has only erred on a couple of occasions from the official Labour Party candidate at any election. Yet the signs are there, as they are all across this economically stagnant post-industrial region, that Labour is beginning to lose its grip in much the same way as it has most definitively in Scotland. Plaid Cymru – the Welsh nationalist party – polled its highest ever in Blaenau Gwent in the 2015 General Election. Yet more worryingly, UKIP received 17.9% of the vote (they got fewer than 500 votes in 2010), fitting the area into the UK-wide narrative of disaffection and mistrust of politics. It’s hardly surprising when the local authority has had to cut £22 million during the last parliament and is looking at a further £18 million in cuts in the next three years – this in an area with the highest rate of unemployment, and thus a high reliance on public services, in Wales.

And yet it seemed that Corbyn’s speech marked an important moment for the large crowd filling the small area of grass around the stones. It was not a call, like the one Gordon Brown hysterically issued before the 2010 election, for the people to come home to Labour, but finally a sign that Labour might be about to come home to them. The New Labour election machine has of course always relied on old Labour constituencies to keep on voting for them and not notice that the party’s policy objectives had long departed from any real efforts to transform, modernise and reinvigorate these post-industrial areas. People are now noticing, and it seems just as imperative for Labour to ensure these safe seats do not fall away as it is to regain Tory-held constituencies. Kendall, Cooper and Burnham are right – Labour’s crisis is real – but they might look for its centre as much in the Rhondda as in Nuneaton.

Aneurin Bevan speaking outside Tredegar, 1960

Corbyn’s team are acutely aware of this, and his speech grounded itself securely in the past victories of the Labour Party for the working classes, working its way into people’s memories of a Labour Party that truly was part of their everyday lives. Aneurin Bevan was at the centre of the speech, tracing his radical values through his actions in creating the NHS, working out how to recast these values in our current situation. The usual issues were raised: tax evasion, a fair deal on energy prices through renationalisation, the restoration of meaningful work and dignity to communities left behind by neoliberalism. The audience played along – they have been waiting for this for decades now – and some even were in tears. The emotional effect was produced not by Corbyn’s rhetoric (as with all his speeches, the emphasis was on clarity of idea rather than perfect delivery) but by a politician articulating their own grievances and sufferings eloquently, inclusively (Corbyn’s ‘we’ is a powerful rhetorical motif) and, most importantly, with hope, at last, for an alternative.

The Corbyn Campaign has captured that which the Left so often fails to grasp (most obviously with Miliband’s recent campaign): a balance between policy specifics and wider brushstrokes. Too often the Left explains to people how they will be helped, what the state can do to improve their lives, what taxes will be levied on which houses to hire how many nurses, but fails utterly to articulate a vision, a set of values, an idea of what the relationship between the people and the state should mean. At the stones, people saw politics talking to them eye to eye about how their values can be the foundations of a modern state. It is at that point, invigorated by the reflection of a set of values close to them, that people may actually begin to engage with the specifics of renationalisation, of ‘people’s QE’. One woman, in conversation with Corbyn, emotionally told him that because of his campaign, not only did she develop an interest in politics but now wanted to become a local politician – she is a stay-at-home mother-of-three.

Critics of the Labour left say that people do not want a ‘hand-out state’ – and gesture vaguely at ‘aspiration’ instead – but they fail to realise that they have been providing hand-out politics, with no direct communication with the people. Corbyn’s campaign, offering a return to grassroots Labour organisation, community politics and real democracy restored to the party, radically destabilises this way of doing business, and in doing so it begins to allow a collective critique of the very business of politics too.

Merlin Gable is an undergraduate at Wadham College and was Editor of Oxford Left Review 15.

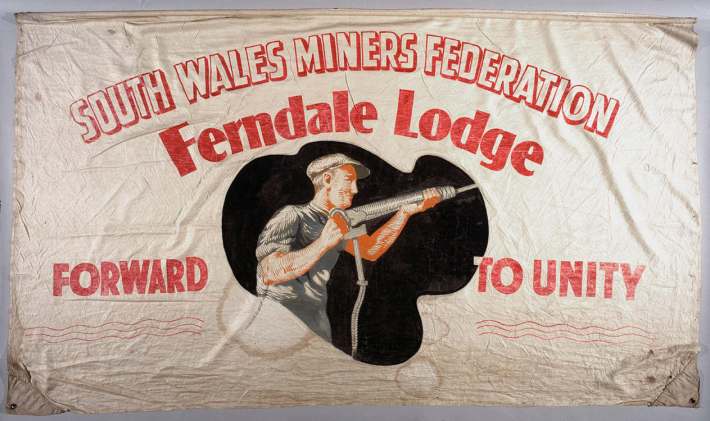

Banner of the Ferndale Lodge of the South Wales Miners Federation, c. 1940 (University of Wales)